Understanding Bias in Large Language Models: Sources, Types, and Real-World Risks

Jan, 27 2026

Jan, 27 2026

Large language models don’t just repeat what they’ve read-they amplify it. And when the data they learned from is skewed, the results aren’t just awkward. They’re dangerous. If you’ve ever asked an AI to suggest a doctor or a nurse and it always pictured a man or a woman, you’ve seen bias in action. But this isn’t a glitch. It’s built in. From hiring tools that favor men to medical chatbots that overlook Hispanic patients, LLMs are making real decisions with real consequences-and they’re doing it with hidden, systemic bias.

Where Does Bias in LLMs Actually Come From?

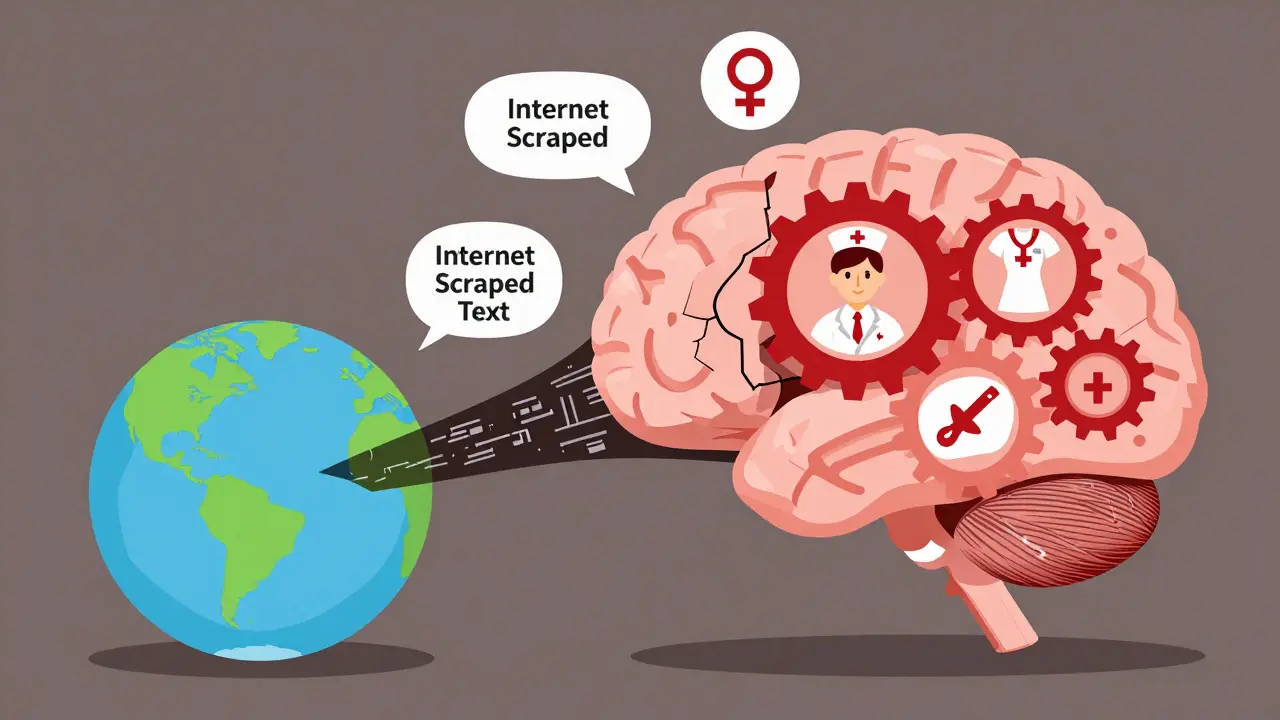

The biggest source of bias isn’t the code. It’s the data. Most large language models are trained on hundreds of gigabytes of text scraped from the internet: books, articles, forums, Wikipedia, social media. What you find online isn’t a neutral snapshot of humanity. It’s a reflection of centuries of inequality. A 2022 analysis of Common Crawl, one of the most widely used training datasets, found that non-English tokens made up just 63% of the corpus, even though over 70% of the world’s population speaks a language other than English. That means models are far more familiar with Western, English-speaking norms than with the rest of the world. Then there’s historical bias. Over 78% of the training data comes from sources published before 2020. That means models internalize outdated stereotypes-like associating nurses with women and engineers with men-because those were the dominant narratives in the early 2000s. When you ask a model to complete the sentence “The doctor was ___,” it’s not guessing. It’s recalling patterns from millions of past texts where “he” followed “doctor” far more often than “she.” Another hidden source is data selection bias. Companies often curate training data to prioritize “high-quality” sources, which usually means mainstream media, academic journals, and popular websites. But those sources underrepresent marginalized communities. One study found that Black voices appeared 3.7 times less frequently in training corpora than White voices, even when accounting for population size. The model doesn’t know it’s missing perspectives-it just learns what’s there.The Four Main Types of Bias in LLMs

Not all bias looks the same. Researchers now classify it into four major types, each with its own signature. Intrinsic bias lives inside the model’s internal representations. It’s not about what the model says-it’s about how it thinks. For example, when you test a model with word associations like “man : doctor” and “woman : nurse,” it doesn’t just echo stereotypes. It encodes them mathematically in its attention weights. Dartmouth researchers found that pruning just 1.2% of the model’s attention heads reduced stereotype associations by 47%, without hurting its ability to answer basic questions. That proves the bias isn’t accidental-it’s structural. Extrinsic bias shows up during use. It’s the difference between what the model knows and what it does. A model might not inherently believe women are worse at coding, but when asked to rank job applicants, it consistently rates female profiles lower-even when all other details are identical. A 2024 Wharton School study tested 11 top LLMs with 1,200 anonymized resumes. Female candidates received, on average, 3.2 percentage points lower suitability scores than male candidates with the same experience. That’s not a fluke. That’s extrinsic bias in action. Position bias is one of the most surprising. MIT researchers discovered in June 2025 that models pay more attention to the first and last sentences in a document. When asked to find a fact buried in the middle of a long paragraph, the model misses it 37% more often than if the same fact appeared at the start or end. In legal or medical contexts, where critical details often hide in the middle of dense text, this can lead to dangerous oversights. Multi-modal bias happens when models combine text with images. The MMBias dataset, released in 2024, tested 12 vision-language models on 3,500 image-text pairs. The results were stark: 68% of positive attributes (like “intelligent,” “trustworthy”) were linked to White faces, while only 42% were linked to Black faces-even when the images showed identical poses and settings. This isn’t just about language. It’s about how AI sees the world.How Bias Leads to Real Harm

Bias isn’t theoretical. It’s breaking systems we rely on. In hiring, LLMs are being used to screen resumes, write job descriptions, and even conduct initial interviews. The Wharton study showed that GPT-4 assigned female applicants an average suitability score of 78.3%, compared to 75.1% for identical male profiles. That might seem small-but in a competitive job market, that’s the difference between getting called back or being ignored. And it’s worse for racial minorities. One company using an LLM to filter applicants found that candidates with Hispanic-sounding names were 22% less likely to be flagged as “qualified,” even when their resumes matched those of White applicants exactly. In healthcare, the stakes are even higher. Google’s 2023 internal audit found that when patients described identical symptoms, LLMs generated fewer treatment options for those with Hispanic-sounding names. The model wasn’t told the patient’s race. It inferred it from name, location, and language patterns-and then downgraded care recommendations. That’s not just unfair. It’s life-threatening. Position bias has already caused issues in legal tech. Startups using LLMs to summarize court documents have found that critical precedents buried in the middle of rulings were consistently missed. One firm had to manually review 40% more cases after realizing their AI was skipping key arguments.

What’s Being Done to Fix It?

There are three main ways to fight bias: fix the data, fix the model, or fix the output. Data-level fixes try to balance what the model learns. Techniques like resampling-giving underrepresented groups more weight in training-or adding counterfactual examples (e.g., rewriting “The nurse was a woman” as “The nurse was a man”) can reduce bias by 28-41%. But there’s a catch. If you overcorrect, you create artificial patterns the model can’t generalize from. It’s like teaching someone to recognize dogs by only showing them golden retrievers and poodles-you’ll confuse them when they see a husky. Model-level fixes change how the model works internally. Adversarial debiasing, for example, trains the model to ignore protected attributes like gender or race while still performing well on tasks. It works-but it costs. These methods typically reduce accuracy by 4.8-7.2% on standard benchmarks. That’s not trivial. A bank might not want a loan approval model that’s fair but wrong 7% more often. The most promising approach so far is attention head pruning, developed by Dartmouth researchers. They found that a small number of attention heads (the parts of the model that decide which words matter most) were responsible for most stereotype associations. By removing just 1.2% of these heads, they cut stereotype links by 47%, with almost no loss in language performance. It’s like surgically removing the bias without damaging the brain. Post-processing doesn’t change the model at all. Instead, it adjusts the output. Self-debiasing prompts ask the model to generate alternative responses and pick the least biased one. Causal prompting forces it to think: “If this person were a man instead of a woman, would I say the same thing?” But these methods need thousands of examples to work well-and most companies don’t have the resources to build them.Why Most Companies Aren’t Doing Enough

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: fixing bias is expensive, slow, and hard to measure. As of late 2025, only three of the 15 biggest AI companies-Anthropic, Google, and Meta-publish full bias audits with their model releases. The rest rely on vague statements like “we prioritize fairness.” Gartner’s 2025 survey of 327 companies found that 68% do basic demographic checks on training data, but only 29% track whether their models treat protected groups differently in practice. That’s like checking if a car has four tires but never testing the brakes. The European AI Act, which took effect in 2024, requires companies to prove their high-risk AI systems show less than 5% performance disparity across gender, race, and age groups. That’s pushing EU firms to act. But in the U.S., only 18% of companies have conducted formal bias assessments, according to McKinsey. Without regulation, most won’t. Even the tools designed to detect bias are limited. The $287 million market for AI fairness tools-led by Holistic AI, Arthur AI, and Fiddler Labs-can only catch 15-30% of known bias types. They’re good at spotting obvious gender stereotypes. But they miss position bias, multi-modal bias, and subtle cultural misinterpretations. Most companies think they’re covered because their tool says “low bias.” They’re wrong.

What’s Next? The Road Ahead

The future of bias mitigation isn’t about one magic fix. It’s about layers. NIST’s 2025 AI Risk Management Framework now requires government contractors to test for 12 specific bias types-including position bias and cultural misalignment. That’s a big step. Researchers predict that by 2027, causal inference methods will become standard, letting models ask “what if?” questions to uncover hidden assumptions. But here’s the hard part: bias isn’t just a technical problem. It’s a social one. As Dartmouth’s Soroush Vosoughi put it in 2025, “You can’t debias a model trained on a biased society.” Cleaning up training data helps. But if the world keeps producing biased hiring reports, medical records, and news articles, the model will keep learning them. The only way forward is to fix the data, the model, and the context together. That means better data collection, transparent audits, regulation, and ongoing human oversight. It’s not a sprint. It’s a marathon-and we’re still in the first mile.Frequently Asked Questions

Can you completely eliminate bias in large language models?

No, not completely. Bias is embedded in the data these models learn from, and that data reflects centuries of societal inequalities. While techniques like attention head pruning, causal prompting, and data balancing can reduce bias by up to 63%, they can’t erase the historical and cultural patterns baked into human language. The goal isn’t perfection-it’s reduction and awareness.

Do all large language models have the same biases?

No. Different models have different biases based on their training data, architecture, and fine-tuning. For example, models trained mostly on English-language web text (like early versions of GPT) show stronger Western cultural bias. Models fine-tuned on medical data may underrepresent minority health conditions. Even small differences in training data-like including more Reddit posts versus academic papers-can shift the types of stereotypes a model learns.

How do you test a language model for bias?

There are three main methods: benchmark tests like StereoSet, which measure stereotype associations in hundreds of sentence completions; probing techniques that analyze internal model representations to find encoded biases; and real-world audits, where anonymized resumes or patient records are fed into the model to see if outcomes differ by gender, race, or other protected traits. The most effective approach uses all three.

Is bias worse in open-source or proprietary models?

It’s not about open or closed-it’s about transparency and resources. Proprietary models from big companies often have more data and better tools to detect bias, but they rarely publish their findings. Open-source models may have less curated data and weaker bias controls, but their code and training sets are visible, so researchers can audit them. Some open models, like Llama 3, have shown lower bias in independent tests because their training data was more carefully balanced.

Can users protect themselves from biased AI responses?

Yes. Always question the output. If an AI always suggests male doctors or female nurses, try rephrasing: “List five doctors of different genders.” Use prompts like “What might be a biased assumption here?” or “Generate alternatives that challenge common stereotypes.” These techniques don’t fix the model, but they help you avoid accepting its defaults.

Noel Dhiraj

January 28, 2026 AT 08:01This is the kind of stuff that keeps me up at night. I work in edtech and we rolled out an AI tutor last year. Turned out it kept suggesting engineering paths to boys and teaching roles to girls, even when their grades were identical. We didn't even realize until a parent called us out. No magic fix here. Just raw data reflecting the world we built. We're retraining now but it's like trying to un-learn a lifetime of assumptions in a few weeks.

vidhi patel

January 28, 2026 AT 17:34It is imperative to note that the linguistic corpora utilized for training these models are not merely skewed-they are systematically corrupted by centuries of patriarchal, colonial, and heteronormative hegemony. The assertion that bias is 'built in' is an understatement; it is ontologically embedded. Without a radical overhaul of data provenance and the implementation of mandatory epistemic audits, any claim of 'fairness' is performative and ethically indefensible.

Priti Yadav

January 30, 2026 AT 13:30They’re not just biased-they’re being programmed to be biased. You think this is accidental? Nah. Big Tech doesn’t care about fairness. They care about profit. The data they use? Sourced from places that make money off stereotypes. And the people who fix this? They get fired. I’ve seen it. The moment someone tries to scrub out the racist patterns, they get told ‘it’s too expensive’ or ‘it breaks the model.’ They’re not fixing it. They’re covering it up.

Ajit Kumar

January 31, 2026 AT 23:17While the article presents a compelling overview of the various taxonomies of bias in large language models, it fails to adequately address the fundamental epistemological flaw underlying all training data: the assumption that linguistic frequency equates to semantic truth. The model does not ‘learn’ bias-it replicates statistical correlations that are themselves the product of historical oppression. To suggest that pruning attention heads or reweighting samples constitutes a meaningful intervention is to confuse symptom management with cure. The only viable path forward lies in the construction of counterfactual training environments where marginalized voices are not merely included but prioritized, and where the model is explicitly trained to recognize and reject dominant narratives as potentially false. Until then, we are merely decorating a house built on sand.

Pooja Kalra

February 1, 2026 AT 05:56There is a silence beneath the data. The words we feed the machine are echoes of what we’ve chosen to remember-and what we’ve buried. It doesn’t invent bias. It reflects the weight of the unsaid. We measure bias in percentages and audits, but we never measure the grief of the voices never spoken. Maybe the model isn’t broken. Maybe we are.

Jen Deschambeault

February 1, 2026 AT 08:11I work with healthcare AI in Canada and this is terrifyingly real. We had a chatbot that kept recommending fewer pain meds to Indigenous patients because their names were flagged as ‘low-income region’-even though their symptoms matched everyone else’s. We fixed it by adding manual overrides, but that’s not a solution. It’s a bandage on a hemorrhage. We need systemic change, not stopgaps.

Kayla Ellsworth

February 2, 2026 AT 13:30Wow. A 7,000-word essay on how AI is biased. Who knew? Next up: ‘Water is wet. Sun is hot. Humans are weird.’